The first net-zero development in Selah, Washington, is a study in compromise—between one team’s vision and the home-buying market at hand

Steve Weise is trying to move the needle. A seasoned builder, first-time developer, and owner of Leading Force Energy & Design Center based in Yakima, Washington, he finds himself in the role of educator more often than not. He describes the region in which he lives and works as having an agricultural history and its demographic as “less educated on the benefits of healthy materials and design.” Therein lies his struggle. “Yakima builders are not sold on the idea that green building is important,” he says. “It’s really code-driven.”

Part of the impetus for opening the 2500-sq.-ft. design center was the fact that Weise was having a hard time sourcing local, sustainable, and healthy materials; he had to trek to Seattle to find them, and he wanted the same availability in Yakima county. Today, the firm is a resource for finding both green building professionals and products that range from cabinetry to flooring, lighting, sound technology, air-sealing supplies, and beyond. The team of designers and tradespeople specializes in the design/build of energy-smart homes, and it offers professional education sessions on energy efficiency and code. “The collaborative model is a way to provide integrative design on a smaller scale,” says Terry Phelan, principal of Living Shelter Architects and an early member of the team.

Setting the stage for future development

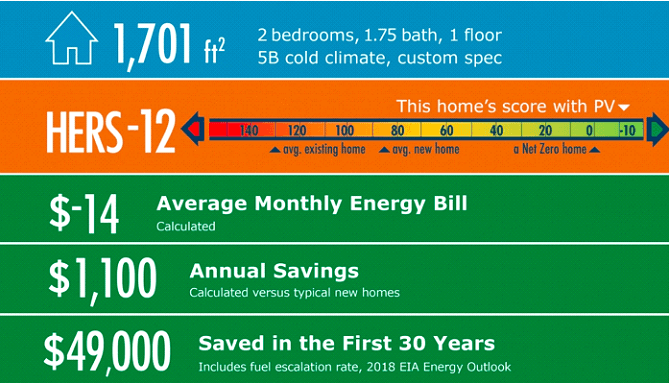

Leading Force’s latest and most ambitious undertaking, Selah Vista Homes, is a 60-home Built Green 5-Star neighborhood development set on a 16 acres. (The project received the 2018 Department of Energy Housing Innovation Award for spec-built houses.) There are five phases of development slated, the first of which calls for 20 new homes. Currently, eight have been built and 13 lots have sold. Weise anticipates selling all lots in three years, and having them built out in five. He is concentrating on pre-sales to keep things rolling forward. For the same reason, he has diversified his strategy to include a mix of custom, spec, prefab, and duplex homes. Opening the pool to include different building types, he believes, helps with the problem of limited resources and the shortage of qualified green-building contractors. For example, Alegis Construction is coming in to build some modular homes—and it is looking to build a plant in Yakima for Built Green 5-Star—or similar third party−verified certification—prefabs.

Given the medley of home types and subcontractors, there are CC&Rs in place to ensure energy, water, materials, and human health requirements are met—those are nonnegotiable. They also protect the vernacular southwest-style architecture and the use of common areas. Phelan, who helped write the CC&Rs, says: “It’s not a free for all, but it’s open to interpretation. We wrote them to set future expectations, so any custom builder coming into the project will be able to keep things in line with the health and energy efficiency goals.”

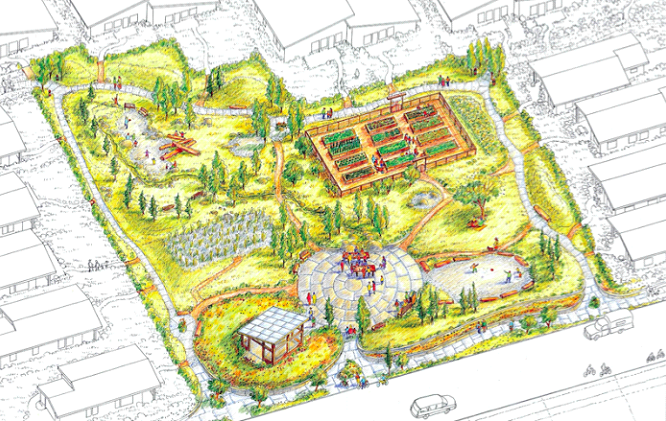

The project employs basic low-impact development (LID) strategies: Homes are clustered with small yards and shared open spaces; lawn areas are limited to 150 sq. ft. per home, and the remainder of the land must be xeriscaped with native or drought-tolerant plants; rain/snowmelt runoff is handled with bioswales; and all outdoor lighting, including the street lighting, is dark-sky compliant.

According to Phelan, “Yakima is a magnet for Seattleites looking to retire where the sun shines.” That target demographic informed the design of the two-bedroom model house (pictured here), which is simple in form and built for universal accessibility with features like level thresholds and entries, extra-wide doorways, and ADA-compliant bathrooms. “We were given license to include things that we thought were important that we haven’t been able to incorporate into a builder package before,” she notes, giving the examples of a super-insulated envelope, clay-plaster walls, daylighting from two sides of every room, and covered outdoor areas on the south side, which allow low winter sun to penetrate the house while also protecting from summer heat gain.

Construction and systems

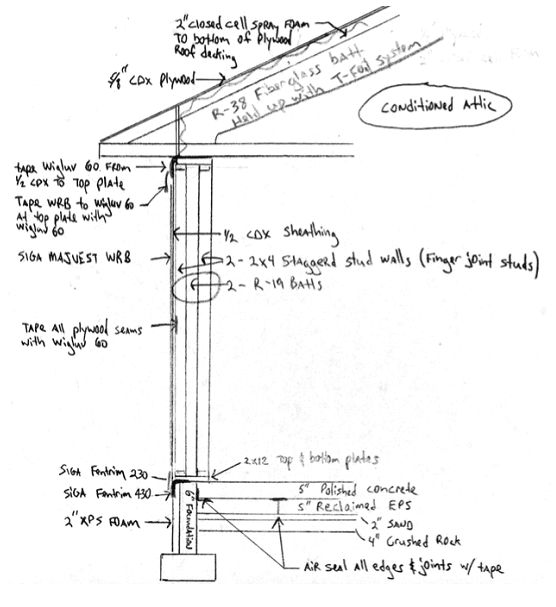

The R-45 wall, R-52 ceiling, and R-20 foundation assemblies are unique to the arid-desert climate. Weise puts the vapor retarder and the air barrier on the exterior, which works in a region with low moisture. He tapes all seams with Siga air-sealing products, and the moisture sensors that he puts in the walls have indicated zero issues over the last three years. “Taping is one of the best tricks out there,” he says. “I don’t depend on the air barrier.” (Blower door tests performed when the sheathing is up measure between .5 and .7 ACH50.)

Of his assemblies, Weise says: “I believe we need to build homes that can be retrofitted. You need to be able to change technologies. I do 100% conditioned attic spaces. I insulate with spray foam to the underside of the roof, which means I don’t have to worry about lighting penetrations. Everything above the sheetrock ceiling is designed to be moved around and changed.” Well aware of the controversy around conditioned attic spaces and spray foam, Weise says: “There are ways to insulate the attic with environmentally sensitive products but it is going to cost you twice the amount to do it.” It is one of the compromises he finds himself forced to make.

The original design called for a hemp-block foundation but the team decided it was too new and risky a product. Instead they used the 12-in. platform for 2×4 double-stud staggered walls. “It was absolutely the best way to get builders to see that they could do this,” Weise notes. The foundation includes 5 in. of recycled EPS foam beneath the slab; and low-maintenance/fire-resistant exterior surfaces include stucco, stone, natural hydraulic lime siding, and corrugated metal. Weiss is a fan of fiberglass Alpen windows and doors, which he describes as the “Maserati of American-made windows.” The triple-pane windows have a .16 U-value or less; doors measure .20. He uses VOC-absorbing Certainteed AirRenew Drywall as well as noise-reducing Certainteed Silent FX.

Weise works with Don Jordan, a member of Insulate America, who has convinced him to use fiberglass batts over cellulose. (Jordan did not respond for comment.) Among his arguments, Weise says, is that when cellulose runs short on supply, it is substituted with cellulose from sources that use a lot of ink, which can be toxic. “He has seen the cellulose industry create havoc,” Weiss explains. “And paper requires some use of fungicide to prevent mold. I would prefer to use Havloc wool over fiberglass batts but I can’t convince people to do that. I did it for one client because it was requested, but I don’t want to marginalize builders. I want them to come by and see something they feel they could do too.”

Sensitivity to homeowner health

Weise prioritizes human health above all else. It is the primary motivation behind his commitment to green building—even in a region where support for it is marginal, at best. “I really believe you need to put people first,” he notes, “and sometimes the products used in the name of energy efficiency are not the best fit for that goal.” That said, walking the line between his mission and affordability means compromising on things like spray foam.

He recalls the clients whose situation set him on this path, explaining how his involvement with them led to the creation of a program he called Culture of Green. “I went around instructing anyone who would listen to me—businesses, builders, real estate agents, and other people in the building industry, about the importance of building for human and environmental health, as well as for future building codes.”

To optimize occupant health, Weise focuses on HVAC systems and integrated technologies. He specs a Zehnder ERV to meet EPA Indoor airPLUS standards for minimizing airborne pollutants; and a Fantech filter is tied together with the Mitsubishi horizontal ducted mini splits. HEPA-filtered air is brought into the distribution system, and the air is distributed in the same registers. A new product, Airthinx, allows homeowners to monitor indoor air quality at a glance. A Daikin mini-split is used for heating and cooling; and a hybrid heat pump supplies hot water.

Lighting and electromagnetic field wiring are among the things Weiss feels are important to human health. “The science shows that our retinas convert sunlight to melatonin, and if you are not viewing 15 minutes of infrared light everyday, you are not producing enough melatonin to sleep well. That’s why we focus on daylighting. And when it comes to artificial lighting, we use LEDs, though we do offer halogen or incandescent for red-spectrum light; LEDs have the capacity to provide the same, though the technology is not quite there yet.” For daisy chain electrical wiring, he drops the lines from the ceiling so electricity is out of the field of a sleeping person’s brain waves. In some cases, he includes a single switch to turn off all electricity in a room. He explains: “If a person’s head is within proximity of electrons flowing through wires, the science shows disruption in brain waves, which interrupts sleep.”

Neighborhood lifestyle

Outdoor living, walkability, and bucolic views characterize Selah Vista. The two-acre shared space includes wheelchair-accessible perimeter walking trails, a community garden, a children’s nature-focused play area, a butterfly garden, and a pavilion. The City is also developing a separate ADA-compliant park nearby. “I’m looking to build a neighborhood where people want to stay and raise their families,” says Weise. “It’s not just about housing. It’s about creating a product that will pass the test of time.” It was sited toward the same end. Public transportation extends to Selah Loop and Goodlander Road, about a half mile from the neighborhood, and schools and the downtown district are less than a mile away.

Community amenities also include two solar fields located on the sloping south edge of the acreage. They are designed to augment power and to ensure that the entire development is net-zero. All homes have rooftop arrays but for homeowners who are unable to draw enough power from their own panels, they can buy into the community solar. (The home solar system is included in the sale price, and is expected to pay for itself in less than seven years.)

A few of the hurdles

Beyond answering the call for new housing, Weise sees the development as a green-building teaching tool for subcontractors, homebuyers, and real estate professionals. However, he says his biggest challenge is providing early and ongoing subcontractor education. “They are used to working in silos, and with green building they need to learn our team culture. They also need constant reminders about job-site construction-waste recycling.” Homeowner education is critical too—whether it is teaching buyers how to operate new systems and technologies for optimal performance or weighing the benefits of green products (including warranties and maintenance requirements) against conventional materials. Construction has actually been slowed down because the demographic is unfamiliar with his ideas and practices.

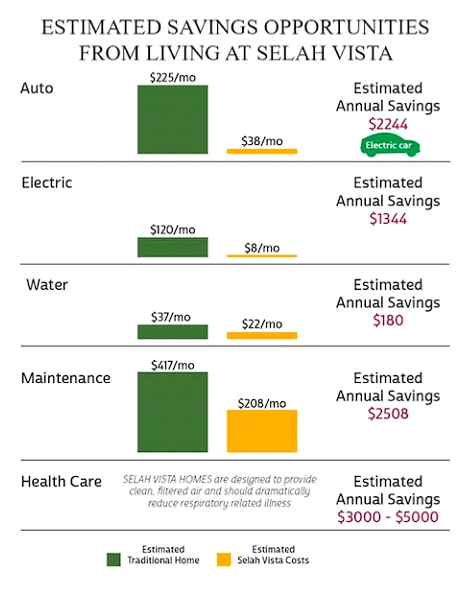

So far, the homes have sold for between $355K and $515K. Asked about their affordability, Weise says: “They are built to last a century, and they have low operating costs and promise good health for occupants. If you do the metrics of what it costs a person who is not healthy to live in an unhealthy environment, they can’t afford not to live in a healthy house.”

On the matter of cost, Phelan weighs in, adding: “I believe Selah Vista could be one model for affordable housing if some of the advanced technologies and product choices were tempered to limit upfront costs. This would be particularly effective in rural communities, where land is available. We have worked with nonprofits and community land trusts, and we know energy efficiency is becoming huge for them; independence in that realm translates to longer-term security and affordability.”